The impact of founder personalities on startup success

Data

Our analysis relies on two datasets. We infer individual personality facets via a previously published methodology20 from Twitter user profiles. Here, we restrict our analysis to founders with a Crunchbase profile. Crunchbase is the world’s largest directory on startups. It provides information about more than one million companies, primarily focused on funding and investors. A company’s public Crunchbase profile can be considered a digital business card of an early-stage venture. As such, the founding teams tend to provide information about themselves, including their educational background or a link to their Twitter account.

We infer the personality profiles of the founding teams of early-stage ventures from their publicly available Twitter profiles, using the methodology described by Kern et al.20. Then, we correlate this information to data from Crunchbase to determine whether particular combinations of personality traits correspond to the success of early-stage ventures. The final dataset used in the success prediction model contains n = 21,187 startup companies (for more details on the data see the Methods section and SI section A.5).

Revisions of Crunchbase as a data source for investigations on a firm and industry level confirm the platform to be a useful and valuable source of data for startups research, as comparisons with other sources at micro-level, e.g., VentureXpert or PwC, also suggest that the platform’s coverage is very comprehensive, especially for start-ups located in the United States21. Moreover, aggregate statistics on funding rounds by country and year are quite similar to those produced with other established sources, going to validate the use of Crunchbase as a reliable source in terms of coverage of funded ventures. For instance, Crunchbase covers about the same number of investment rounds in the analogous sectors as collected by the National Venture Capital Association22. However, we acknowledge that the data source might suffer from registration latency (a certain delay between the foundation of the company and its actual registration on Crunchbase) and success bias in company status (the likeliness that failed companies decide to delete their profile from the database).

The definition of startup success

The success of startups is uncertain, dependent on many factors and can be measured in various ways. Due to the likelihood of failure in startups, some large-scale studies have looked at which features predict startup survival rates23, and others focus on fundraising from external investors at various stages24. Success for startups can be measured in multiple ways, such as the amount of external investment attracted, the number of new products shipped or the annual growth in revenue. But sometimes external investments are misguided, revenue growth can be short-lived, and new products may fail to find traction.

Success in a startup is typically staged and can appear in different forms and times. For example, a startup may be seen to be successful when it finds a clear solution to a widely recognised problem, such as developing a successful vaccine. On the other hand, it could be achieving some measure of commercial success, such as rapidly accelerating sales or becoming profitable or at least cash positive. Or it could be reaching an exit for foundation investors via a trade sale, acquisition or listing of its shares for sale on a public stock exchange via an Initial Public Offering (IPO).

For our study, we focused on the startup’s extrinsic success rather than the founders’ intrinsic success per se, as its more visible, objective and measurable. A frequently considered measure of success is the attraction of external investment by venture capitalists25. However, this is not in and of itself a good measure of clear, incontrovertible success, particularly for early-stage ventures. This is because it reflects investors’ expectations of a startup’s success potential rather than actual business success. Similarly, we considered other measures like revenue growth26, liquidity events27,28,29, profitability30 and social impact31, all of which have benefits as they capture incremental success, but each also comes with operational measurement challenges.

Therefore, we apply the success definition initially introduced by Bonaventura et al.32, namely that a startup is acquired, acquires another company or has an initial public offering (IPO). We consider any of these major capital liquidation events as a clear threshold signal that the company has matured from an early-stage venture to becoming or is on its way to becoming a mature company with clear and often significant business growth prospects. Together these three major liquidity events capture the primary forms of exit for external investors (an acquisition or trade sale and an IPO). For companies with a longer autonomous growth runway, acquiring another company marks a similar milestone of scale, maturity and capability.

Using multifactor analysis and a binary classification prediction model of startup success, we looked at many variables together and their relative influence on the probability of the success of startups. We looked at seven categories of factors through three lenses of firm-level factors: (1) location, (2) industry, (3) age of the startup; founder-level factors: (4) number of founders, (5) gender of founders, (6) personality characteristics of founders and; lastly team-level factors: (7) founder-team personality combinations. The model performance and relative impacts on the probability of startup success of each of these categories of founders are illustrated in more detail in section A.6 of the Supplementary Information (in particular Extended Data Fig. 19 and Extended Data Fig. 20). In total, we considered over three hundred variables (n = 323) and their relative significant associations with success.

The personality of founders

Besides product-market, industry, and firm-level factors (see SI section A.1), research suggests that the personalities of founders play a crucial role in startup success19. Therefore, we examine the personality characteristics of individual startup founders and teams of founders in relationship to their firm’s success by applying the success definition used by Bonaventura et al.32.

Employing established methods33,34,35, we inferred the personality traits across 30 dimensions (Big Five facets) of a large global sample of startup founders. The startup founders cohort was created from a subset of founders from the global startup industry directory Crunchbase, who are also active on the social media platform Twitter.

To measure the personality of the founders, we used the Big Five, a popular model of personality which includes five core traits: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Emotional stability. Each of these traits can be further broken down into thirty distinct facets. Studies have found that the Big Five predict meaningful life outcomes, such as physical and mental health, longevity, social relationships, health-related behaviours, antisocial behaviour, and social contribution, at levels on par with intelligence and socioeconomic status36Using machine learning to infer personality traits by analysing the use of language and activity on social media has been shown to be more accurate than predictions of coworkers, friends and family and similar in accuracy to the judgement of spouses37. Further, as other research has shown, we assume that personality traits remain stable in adulthood even through significant life events38,39,40. Personality traits have been shown to emerge continuously from those already evident in adolescence41 and are not significantly influenced by external life events such as becoming divorced or unemployed42. This suggests that the direction of any measurable effect goes from founder personalities to startup success and not vice versa.

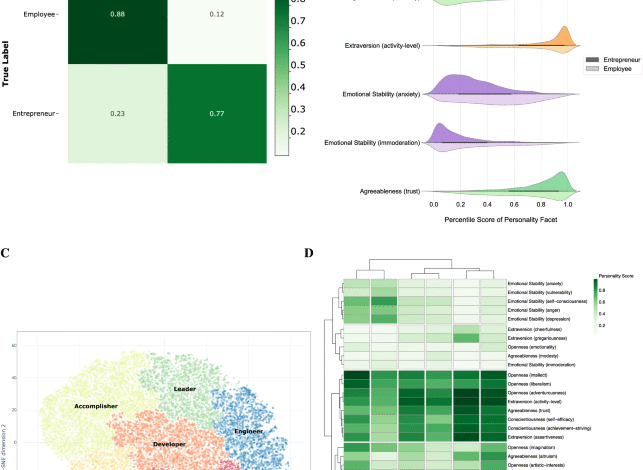

As a first investigation to what extent personality traits might relate to entrepreneurship, we use the personality characteristics of individuals to predict whether they were an entrepreneur or an employee. We trained and tested a machine-learning random forest classifier to distinguish and classify entrepreneurs from employees and vice-versa using inferred personality vectors alone. As a result, we found we could correctly predict entrepreneurs with 77% accuracy and employees with 88% accuracy (Fig. 1A). Thus, based on personality information alone, we correctly predict all unseen new samples with 82.5% accuracy (See SI section A.2 for more details on this analysis, the classification modelling and prediction accuracy).

We explored in greater detail which personality features are most prominent among entrepreneurs. We found that the subdomain or facet of Adventurousness within the Big Five Domain of Openness was significant and had the largest effect size. The facet of Modesty within the Big Five Domain of Agreeableness and Activity Level within the Big Five Domain of Extraversion was the subsequent most considerable effect (Fig. 1B). Adventurousness in the Big Five framework is defined as the preference for variety, novelty and starting new things—which are consistent with the role of a startup founder whose role, especially in the early life of the company, is to explore things that do not scale easily43 and is about developing and testing new products, services and business models with the market.

Once we derived and tested the Big Five personality features for each entrepreneur in our data set, we examined whether there is evidence indicating that startup founders naturally cluster according to their personality features using a Hopkins test (see Extended Data Figure 6). We discovered clear clustering tendencies in the data compared with other renowned reference data sets known to have clusters. Then, once we established the founder data clusters, we used agglomerative hierarchical clustering. This ‘bottom-up’ clustering technique initially treats each observation as an individual cluster. Then it merges them to create a hierarchy of possible cluster schemes with differing numbers of groups (See Extended Data Fig. 7). And lastly, we identified the optimum number of clusters based on the outcome of four different clustering performance measurements: Davies-Bouldin Index, Silhouette coefficients, Calinski-Harabas Index and Dunn Index (see Extended Data Figure 8). We find that the optimum number of clusters of startup founders based on their personality features is six (labelled #0 through to #5), as shown in Fig. 1C.

To better understand the context of different founder types, we positioned each of the six types of founders within an occupation-personality matrix established from previous research44. This research showed that ‘each job has its own personality’ using a substantial sample of employees across various jobs. Utilising the methodology employed in this study, we assigned labels to the cluster names #0 to #5, which correspond to the identified occupation tribes that best describe the personality facets represented by the clusters (see Extended Data Fig. 9 for an overview of these tribes, as identified by McCarthy et al.44).

Utilising this approach, we identify three ’purebred’ clusters: #0, #2 and #5, whose members are dominated by a single tribe (larger than 60% of all individuals in each cluster are characterised by one tribe). Thus, these clusters represent and share personality attributes of these previously identified occupation-personality tribes44, which have the following known distinctive personality attributes (see also Table 1):

-

Accomplishers (#0)—Organised & outgoing. confident, down-to-earth, content, accommodating, mild-tempered & self-assured.

-

Leaders (#2)—Adventurous, persistent, dispassionate, assertive, self-controlled, calm under pressure, philosophical, excitement-seeking & confident.

-

Fighters (#5)—Spontaneous and impulsive, tough, sceptical, and uncompromising.

We labelled these clusters with the tribe names, acknowledging that labels are somewhat arbitrary, based on our best interpretation of the data (See SI section A.3 for more details).

For the remaining three clusters #1, #3 and #4, we can see they are ‘hybrids’, meaning that the founders within them come from a mix of different tribes, with no one tribe representing more than 50% of the members of that cluster. However, the tribes with the largest share were noted as #1 Experts/Engineers, #3 Fighters, and #4 Operators.

To label these three hybrid clusters, we examined the closest occupations to the median personality features of each cluster. We selected a name that reflected the common themes of these occupations, namely:

-

Experts/Engineers (#1) as the closest roles included Materials Engineers and Chemical Engineers. This is consistent with this cluster’s personality footprint, which is highest in openness in the facets of imagination and intellect.

-

Developers (#3) as the closest roles include Application Developers and related technology roles such as Business Systems Analysts and Product Managers.

-

Operators (#4) as the closest roles include service, maintenance and operations functions, including Bicycle Mechanic, Mechanic and Service Manager. This is also consistent with one of the key personality traits of high conscientiousness in the facet of orderliness and high agreeableness in the facet of humility for founders in this cluster.

Founder-Level Factors of Startup Success. (A), Successful entrepreneurs differ from successful employees. They can be accurately distinguished using a classifier with personality information alone. (B), Successful entrepreneurs have different Big Five facet distributions, especially on adventurousness, modesty and activity level. (C), Founders come in six different types: Fighters, Operators, Accomplishers, Leaders, Engineers and Developers (FOALED) (D), Each founder Personality-Type has its distinct facet.

Together, these six different types of startup founders (Fig. 1C) represent a framework we call the FOALED model of founder types—an acronym of Fighters, Operators, Accomplishers, Leaders, Engineers and Developers.

Each founder’s personality type has its distinct facet footprint (for more details, see Extended Data Figure 10 in SI section A.3). Also, we observe a central core of correlated features that are high for all types of entrepreneurs, including intellect, adventurousness and activity level (Fig. 1D).To test the robustness of the clustering of the personality facets, we compare the mean scores of the individual facets per cluster with a 20-fold resampling of the data and find that the clusters are, overall, largely robust against resampling (see Extended Data Figure 11 in SI section A.3 for more details).

We also find that the clusters accord with the distribution of founders’ roles in their startups. For example, Accomplishers are often Chief Executive Officers, Chief Financial Officers, or Chief Operating Officers, while Fighters tend to be Chief Technical Officers, Chief Product Officers, or Chief Commercial Officers (see Extended Data Fig. 12 in SI section A.4 for more details).

The ensemble theory of success

While founders’ individual personality traits, such as Adventurousness or Openness, show to be related to their firms’ success, we also hypothesise that the combination, or ensemble, of personality characteristics of a founding team impacts the chances of success. The logic behind this reasoning is complementarity, which is proposed by contemporary research on the functional roles of founder teams. Examples of these clear functional roles have evolved in established industries such as film and television, construction, and advertising45. When we subsequently explored the combinations of personality types among founders and their relationship to the probability of startup success, adjusted for a range of other factors in a multi-factorial analysis, we found significantly increased chances of success for mixed foundation teams:

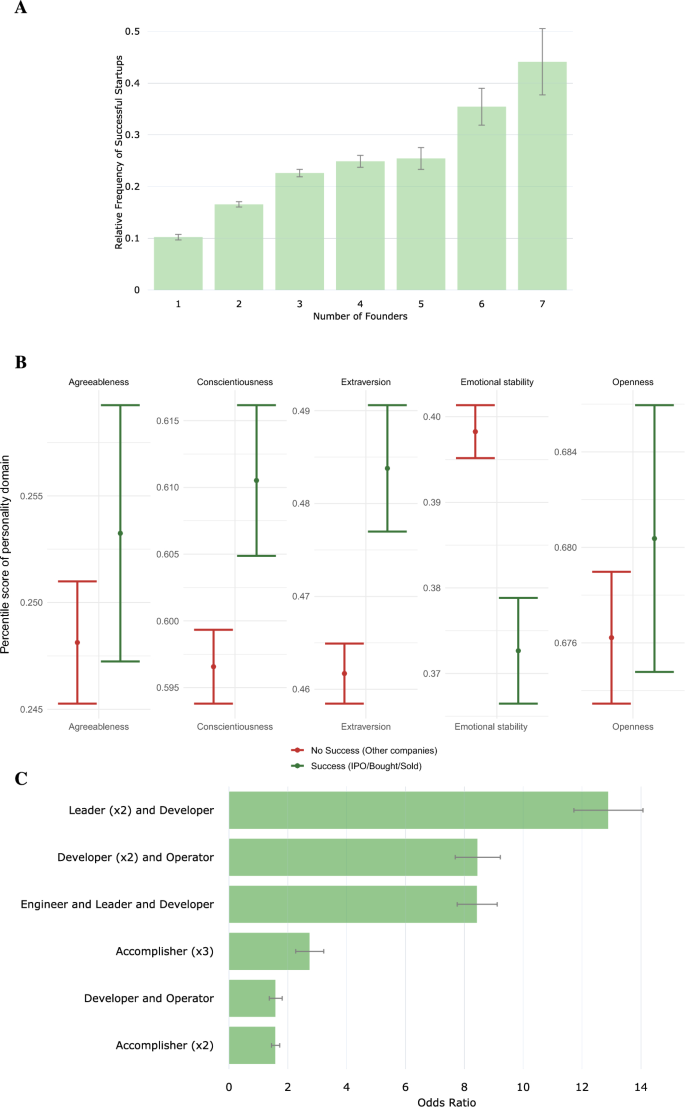

Initially, we find that firms with multiple founders are more likely to succeed, as illustrated in Fig. 2A, which shows firms with three or more founders are more than twice as likely to succeed than solo-founded startups. This finding is consistent with investors’ advice to founders and previous studies46. We also noted that some personality types of founders increase the probability of success more than others, as shown in SI section A.6 (Extended Data Figures 16 and 17). Also, we note that gender differences play out in the distribution of personality facets: successful female founders and successful male founders show facet scores that are more similar to each other than are non-successful female founders to non-successful male founders (see Extended Data Figure 18).

The Ensemble Theory of Team-Level Factors of Startup Success. (A) Having a larger founder team elevates the chances of success. This can be due to multiple reasons, e.g., a more extensive network or knowledge base but also personality diversity. (B) We show that joint personality combinations of founders are significantly related to higher chances of success. This is because it takes more than one founder to cover all beneficial personality traits that ‘breed’ success. (C) In our multifactor model, we show that firms with diverse and specific combinations of types of founders have significantly higher odds of success.

Access to more extensive networks and capital could explain the benefits of having more founders. Still, as we find here, it also offers a greater diversity of combined personalities, naturally providing a broader range of maximum traits. So, for example, one founder may be more open and adventurous, and another could be highly agreeable and trustworthy, thus, potentially complementing each other’s particular strengths associated with startup success.

The benefits of larger and more personality-diverse foundation teams can be seen in the apparent differences between successful and unsuccessful firms based on their combined Big Five personality team footprints, as illustrated in Fig. 2B. Here, maximum values for each Big Five trait of a startup’s co-founders are mapped; stratified by successful and non-successful companies. Founder teams of successful startups tend to score higher on Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Agreeableness.

When examining the combinations of founders with different personality types, we find that some ensembles of personalities were significantly correlated with greater chances of startup success—while controlling for other variables in the model—as shown in Fig. 2C (for more details on the modelling, the predictive performance and the coefficient estimates of the final model, see Extended Data Figures 19, 20, and 21 in SI section A.6).

Three combinations of trio-founder companies were more than twice as likely to succeed than other combinations, namely teams with (1) a Leader and two Developers, (2) an Operator and two Developers, and (3) an Expert/Engineer, Leader and Developer. To illustrate the potential mechanisms on how personality traits might influence the success of startups, we provide some examples of well-known, successful startup founders and their characteristic personality traits in Extended Data Figure 22.

Source link